“What I really wanted to say was that a monster is not such a terrible thing to be. From the Latin root monstrous, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: centaur, griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.” (One Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous pg. 13 – Ocean Vuong)

We are after something better within ourselves and the world. Something hybrid.

We look at pieces of ourselves so as to find that lighter and more complete sense of self, the one we can bring more of to all situations, one that does not mind finagling a costume–a posture, an approach, a tone of voice–so as to lead effectively, serve others, be at ease even amidst what is inherently difficult.

In what way is this hybrid something between old language and new?

“Queen” and “monster” are old words that can be ascribed to how you see (part of) yourself and how you imagine/assume/wish/fear others see you.

“Success,” “failure,” “boss,” “cartoonish” “frightful” “good girl” are newer words that do this too.

The world relies on (and defaults to) old language, old constructions, old power dynamics and our psychology forms (as kids) around conceptions of self that defend us against our fears.

It is thus easy to get caught up in what the world wants or expects, retreat to (or make a habit of) the words the ego thinks it needs from those old days of being young.

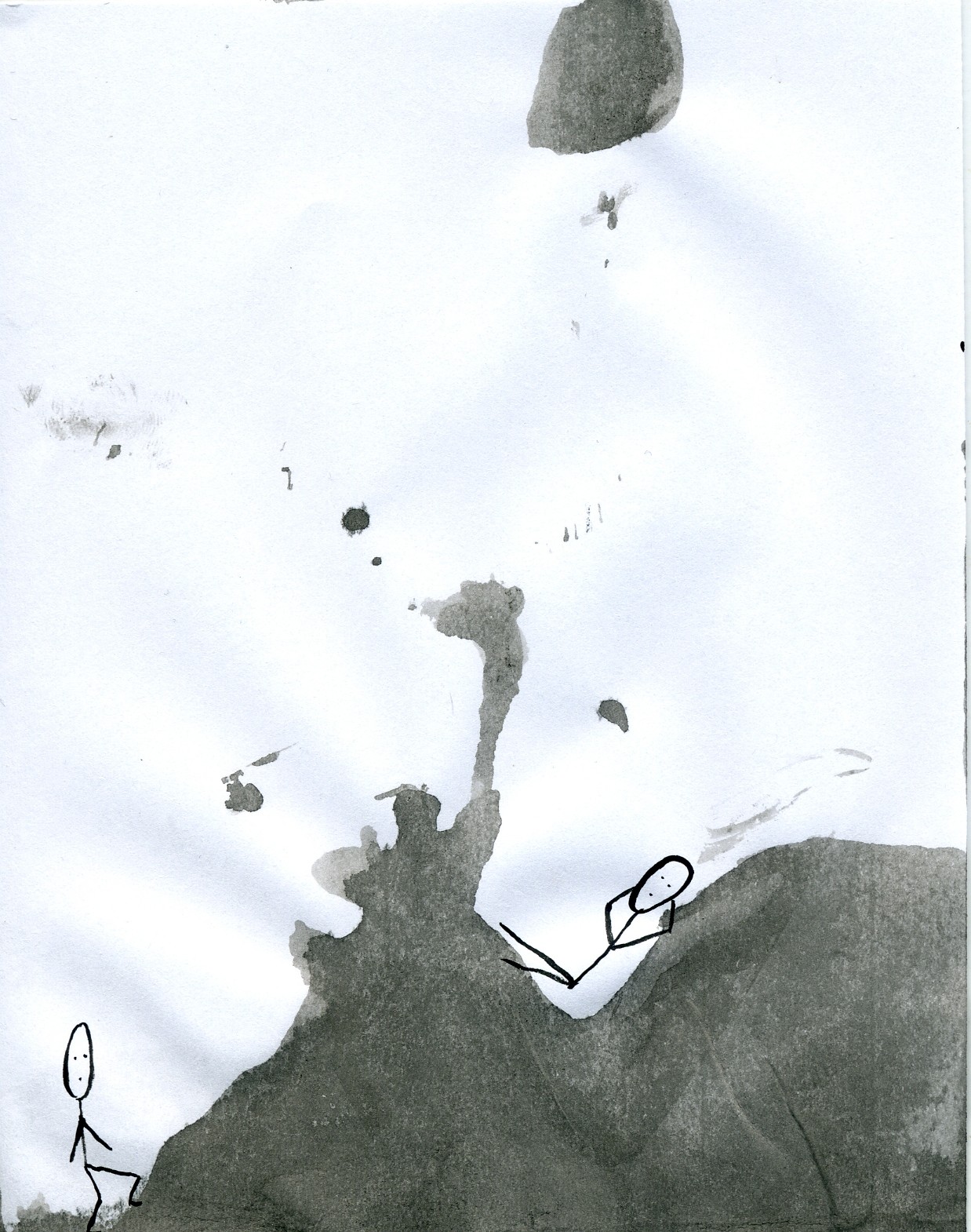

To suggest that our sense of self is enough of a costume that we can wear it internally and play with it there, we’ve written stories about how we costume up our ______ sense of self.

And to see how many words, other than just queen or monster, might go in that blank space is a way of playing, a way of trying on costumes, redefining those senses of self that are handed down to us from some historical or personal past, a move towards gaining the power of self-definition, self-expression too.

It is not that anything can mean anything.

None of us are actual queens or real monsters, and yet we can all feel the implications of such partial or failed words.

Indeed, how brave to show your monster drawing to a group of strangers? How necessary to think as the queen given patriarchal power structures and Disney standards?

But to redefine those old words into private construction means you will not let someone else’s language proscribe for you how you will feel about yourself.

It also means you can begin to shift your attention from the role the world wants you to play to the purpose you wish to serve, from, say, “boss who must be in control” to “poet who offers warning and shelter.”

To put it another way, if we are meant to be dancing in class or at the meeting or in front of our computers or holding the book we read, we must find a way to let that happen.

It is how the partial self becomes whole, even while wearing the costume of a role.